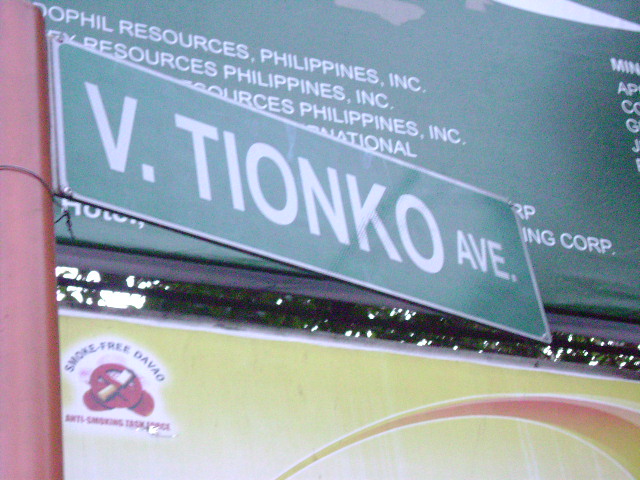

[caption id="attachment_1198" align="aligncenter" width="540" caption="Tionko Ave.---one of the places in Davao City where prostitution is thriving."]

[/caption]

[/caption]“While nothing is easier than to denounce the evildoer, nothing is more difficult than to understand him.”— Fyodor Dostoevsky

“Why not child prostitution?” my research professor asked me and my two group mates, Adam and Mark.

There was a silence. I didn’t know what to say. Adam and Mark didn’t say a word either. They just looked at me, as though they were telling me not to accept our professor’s suggestion. I knew then what they meant, so I told our professor, “We’ll think about it, Sir.”

My group mates handed over me, being the leader of our group, the decision to choose a subject for our research. Early on we decided that we would be doing a research on street children. After all, they are easy to find. They are everywhere. But our professor told us that it’s very common. “Choose something that’s least studied,” he said, “a subject that’s novel.”

When we couldn’t think of a subject aside from what we proposed before, I asked our professor what he could suggest. He suggested child prostitution. “But Sir," I protested, "it would be very difficult for us to do it."

"Who says it would be easy?” he retorted.

Instead of quibbling with my professor, I turned to Adam and Mark and asked them, “Why not give it a try?” I was afraid they would decline, so I was relieved that they didn’t. There was no escaping, however, that both of them were reluctant. So was I.

Then came the time to interview a prostitute, a child prostitute at that. Strangely enough, that day, October 5, was also the day Davao City was celebrating the fourth “No Prostitution Day.”

A local newspaper ran an editorial, saying a day of no prostitution includes “…no prostitution occurring in massage parlors, on the streets, in hotels or everywhere else.” But it was supremely ironic that as the city was celebrating “No Prostitution Day,” prostitution on the streets was very much alive.

[caption id="attachment_1200" align="aligncenter" width="540" caption="Hiding behind the bicycle of the lantern vendor, we took this photo of a patron's SUV stopping by to pick up a prostitute."]

[/caption]

[/caption]I remember it was almost midnight when we arrived in Tionko Avenue—one of the many places in Davao City where prostitution is thriving. When we arrived there, the girls, known in the place as “Chicks,” were already coquettishly plying the street to rope in potential customers. (A slang word, a chick connotes a young and fresh woman, as in a newly hatched chicken.)

“Chicks, Sir?” a lady, who appeared to be a pimp, asked us, pointing to a group of barely clad girls. We ignored her. We walked past the first group until we reached the second group—Cathy’s group. Cathy (not her real name) immediately recognized us. She was wearing a sexy pants and a spaghetti-strap blouse—her everyday outfit.

(We’ve previously arranged an interview with her. Of all the girls we’ve talked to, it was only her who agreed to be interviewed. After all, she’s no stranger to people like us; she was interviewed twice before.)

Cathy was lured into this lurid trade at the age of 12. Was she forced? “Nobody forced me,” she said. “It was only me and my barkada (peers) who made the decision to enter prostitution.” Although we have doubts in our minds, we didn’t bother to ask her.

“Having the kind of work that I have is no picnic,” she said. Although she has been working as such for almost four years and is considered well-versed with the ways of prostitution, she still has to battle against “sadist” customers. “Fortunately,” she said, “the only physical mistreatment I ever got was a slap on my face.”

And there’s the humiliation, too.

“I know very well how people look at me,” she said. “I admit that in the eyes of society, my job is dirty." "

But what can I do?” she asked. “This is the only way I can help my mother since my father is no longer alive, and I couldn’t take other jobs because I am just a high school drop-out.”

“Do you have dreams?” I asked her. Her reply astounded me. “Of course, I do,” she said, her eyes misty and her voice melancholic. “I want to be a nurse someday.”

I was astounded because I thought she would say, “No, I don’t have a dream” or would quip, “Dream, what it is?” I thought girls like her are already resigned to where they are now, to what they are now. I thought they have already lost hope in hoping. I thought they are dreamless. But I was dead wrong.

It's been a year since we interviewed Cathy, but the lessons I learned from that encounter still linger. What started out as an ordinary academic project ended up as a life-altering encounter. Looking back, I realized that had we not accepted our professor’s suggestion, we couldn’t have known that these women have dreams, too. We couldn’t have known that they also long for a better and decent life.

These women are rarely understood and often condemned as a plague that society must get rid of. But if only we will listen to their stories, we will find out that they are not really the kind of people we think they are. They are not that hopeless as we used to think. Just the opposite is true: they are brimming with hope.

And I think it’s not a question if Cathy and other can achieve their dreams but when.

No comments:

Post a Comment